Winter is a perfect time for reading up on all sorts of things. Which in turn is the perfect excuse for curling up on the sofa and not moving an inch for the next three hours. It’s the perfect pastime:

Just a couple of days ago, I ran into a curious thing about numbers. In this case, numbers that reflect the growth of the global human population.

Knowledge… and the thing about population numbers

Far back in time, numbers are partly (or even mostly) based on educated guesses. It’s estimated that about 2000 years ago, the total population on earth of homo sapiens (or at least the species that is assumed, by individuals of that same species, to be able to think), is estimated to have been somewhere around 300 million. Rome hit the 1 million mark around that time.

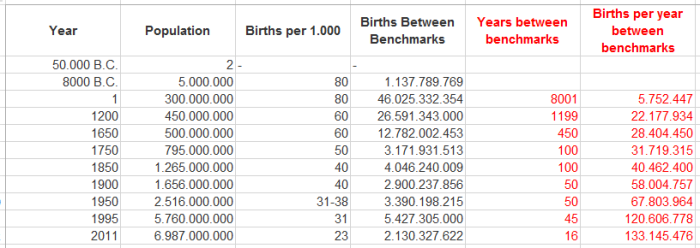

The table contains a set of years for which the population was calculated and/or estimated (like I said, the further back you go, the more guesswork this involves). It also contains the number of births per 1000 individuals. The fourth column contains the number of births between two consecutive benchmarks.

As intriguing as the table (which I found in Gurteen’s Knowledge Newsletter) was, I thought it was lacking something. So I added two more columns, figuring:

- If you have the years and the population size (more or less), you can calculate how many years there are between every two consecutive benchmarks.

- Once you have that, you could even use the number of births between benchmarks and the number of years between benchmarks to come up with…

The number of births per year. And when you see those numbers, you realize two sets of numbers are developing in opposite directions.

Population growth. Black text from David Gurteen’s Knowledge Newsletter; red columns added by me. Click to enlarge.

More or less

- The number of births per 1000 humans per year has gone down in no uncertain way. Actually, I’m guessing it’s even more extreme than it looks, because death rates among young children were very high for a very long time (and among mothers).

- Meanwhile, the absolute number of births per year has gone up as steadily. There are now enough representatives of the human species that not all need to have children at all to sustain the species as a whole – at this rate, only half of all humans will need to reproduce on a moderate scale to keep the population growing.

So… what are the odds of 7 billion human beings having no impact on their environment? (Nope, I’m not adding examples.) On the other hand: if 1 million people decide to rip their lawns out and putting in plants that provide shade and cool spots in the garden instead of trying to keep all those lawns green (and the air conditioning roaring) in another sweltering summer,* that will have an impact, too.

* Not summer around here. We tend to get wet no matter the season. I looked it up last autumn and my hunch was right: we’re in the perfect region to get seriously soaked (as confirmed by 10 year average rainfall stats). I’m not going to risk growing grapes 🙂